History In Photographs

Be sure to check out HIP’s blog each day to learn about daily historical events, to read about featured photos, and to stay updated with current events. You can even become a fellow HIPster by interacting with our content and commenting on our posts with any information or connection you have to our content.

Finding Value in the Journey: Becoming a Personal Property Appraiser

Posted by Megan Shepherd on

Read more

Finding Value in the Journey: Becoming a Personal Property Appraiser

Posted by Megan Shepherd on

On Imperfection: The Importance of "Bad" Photographs

Posted by Megan Shepherd on

Read more

On Imperfection: The Importance of "Bad" Photographs

Posted by Megan Shepherd on

An Introduction to Collecting Photography: A Professional Shares Her Tips

Posted by Megan Shepherd on

Read more

An Introduction to Collecting Photography: A Professional Shares Her Tips

Posted by Megan Shepherd on

Looking at the Past: Vernacular Photography

Posted by Megan Shepherd on

Read more

Looking at the Past: Vernacular Photography

Posted by Megan Shepherd on

Read more

American Hero, American Artist: The Legacy of George Sakata

Posted by Allison Radomski on

This Memorial Day, as our nation honors those who have served in our military, the team at HistoryInPhotographs.com (HIP) would like to use this occasion to share a bit more about one such hero: George Sakata, an American soldier and photographer whose work is featured on our HIP site.

From the Sugarcane Fields of Hawaii to California

George was born in Pocatello, Idaho, in 1922. However, the story of his life and his photographs begins long before his birth. It started in the 1860s when Japanese immigrants began arriving in Hawaii to work on its burgeoning sugar cane plantations. During this chapter, exploitation and hardship were typical for this community. Large commercial interests held serious sway in Hawaii, and the sugar cane industry demanded grueling physical labor from the Japanese workers that it depended upon. Immigrant workers could even be fined or whipped for simply talking or taking a break to stretch during their long, arduous workdays.

It wasn’t until the turn of the century that Japanese immigrant families like George’s began to create homes in the Mainland U.S., mainly along the West coast. Once again, Japanese workers had no choice but to take undesirable jobs in mines and in railroad construction. On top of this physical exploitation, Japanese immigrants experienced broad discrimination. They were barred from citizenship, which meant that they were unable to own any land. They were also barred from participating in the American labor movement, which made it difficult, if not impossible, for them to demand better working conditions and fair wages. Japanese immigrants were also victims of riots and violence, and many communities made it painfully clear that Japanese families were not welcome in their neighborhoods. This is the world that George was born into in 1922.

From Hardworking Immigrant to a U.S. Internment Camp

Although this type of discrimination was the unfortunate norm throughout George’s childhood, the Japanese immigrant community faced even greater struggles in 1942. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the incarceration of Japanese families. As a result of this order, about 120,000 Japanese Americans were forced to leave their homes and relocate to squalid internment camps scattered across the western United States. Relocation also required the forced liquidation of assets, so evacuees had no choice but to sell whatever possessions they couldn’t carry. In exchange, they were placed indefinitely in prison compounds surrounded by snipers and barbed wire.

At that time, George, his parents, and his younger brother lived in Glendale, California. Around his 20th birthday, George and his family arrived at the Manzanar War Relocation Center, an internment camp located just north of Death Valley. Manzanar was an especially difficult camp because of its punishing desert climate. In addition to the camp’s communal latrines and cramped barracks, Manzanar’s prisoners had to deal with scorching temperatures that could reach over 110 degrees Fahrenheit. Relentless desert winds filled the camp with sand and dust, and the winter months were no better. Below-freezing temperatures were common, making the winters just as miserable. By September 1942, around 10,000 Japanese Americans were living at Manzanar.

Internment Camp Prisoner to War Hero

In the early years of World War II, Japanese Americans were prohibited from military service, but by 1943, this policy had changed. More than 30,000 second-generation Americans of Japanese descent — also known as Nisei — served in the United States military during World War II. George Sakata was one of them.

George filled out his draft card in 1942, shortly after his arrival at Manzanar, and within the next year or so, he became a member of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The 442nd RCT was a segregated unit that consisted entirely of Nisei soldiers. Because of their Japanese heritage, these particular soldiers were treated as expendables, and they received especially risky assignments. Even so, the 442nd accepted these challenges, matching the adversities of war with their tenacity. Their motto became “Go for Broke.”

Defying dangerous odds, the Nisei soldiers secured significant victories for the Allied forces. In 1944, the 442nd worked its way across Southern France, liberating various towns from Nazi occupation. They were also active throughout Italy, partnering with the 92nd Infantry Division (a segregated African American soldier unit) to push Nazi forces back across the border.

Perhaps their most famous victory was the successful rescue of the Lost Battalion. In October 1944, the 1st Battalion of the 141st Infantry, also known as the Texas Battalion, became surrounded by German forces in the Vosges Mountains. Although other battalions made multiple rescue attempts, none succeeded. About 275 soldiers were trapped, and their chances of survival became increasingly grim.

The 442nd RCT was sent in as a last-ditch effort to save the doomed battalion. After several days of harrowing combat, the 442nd broke through the German forces and rescued the 211 surviving members of the Lost Battalion. During their entire Vosges campaign, which also included the liberation of Bruyeres and Biffontaine,160 members of the 442nd RCT were killed, and 1,200 were wounded.

It would not be the first or the last time that these Nisei soldiers would take great risks and suffer severe casualties on behalf of their country. In recognition of their bravery, the unit was awarded more than 4,000 Purple Hearts, 560 Silver Star Medals, and 21 Medals of Honor. To this day, the 442nd remains the most decorated unit for its size and length of service in all of U.S. military history.

George Sakata was one of these men. Like so many Nisei soldiers, he served his country courageously and made incredible sacrifices for the United States. After World War II, George returned home to the U.S. He married, had children, and built a career as a mechanical engineer.

A Fresh Perspective on the War

Here at HIP, we don’t know as much about George’s story as we might like, primarily because he, like so many Nisei veterans, didn’t talk to his family and friends about his accomplishments or the dangers of his deployment. While we were able to find some of his family online and also discover more information via Ancestry, George passed away in 2009, so there is much that we can never know about him—which is one reason why we’re so excited about George’s photographs.

George was an avid photographer throughout his life, and he had his camera with him during his deployment. After George’s death, HIP’s founder and WorthPoint CEO, Will Seippel, purchased the bulk of George’s photographic negatives, and these include the snapshots that he took throughout World War II.

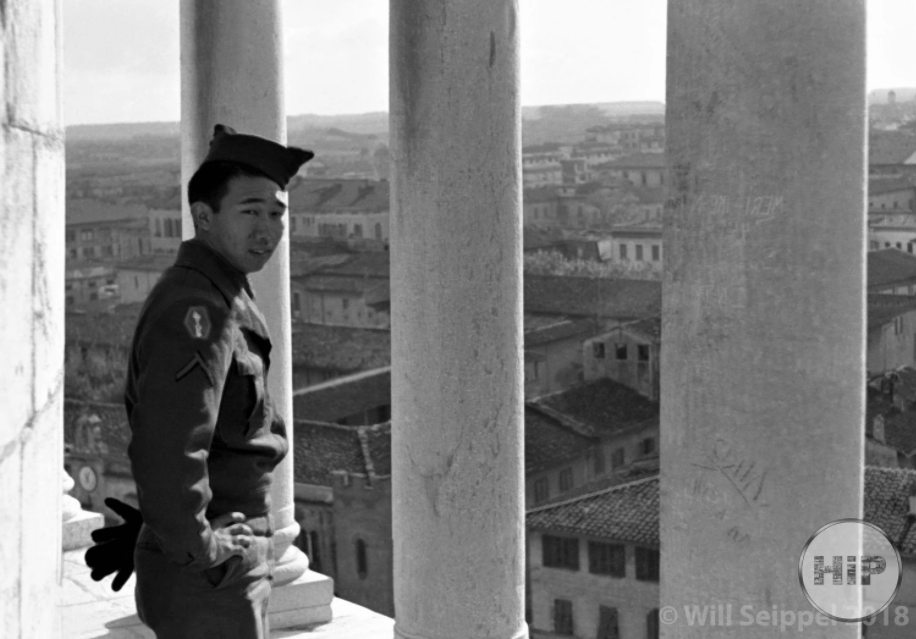

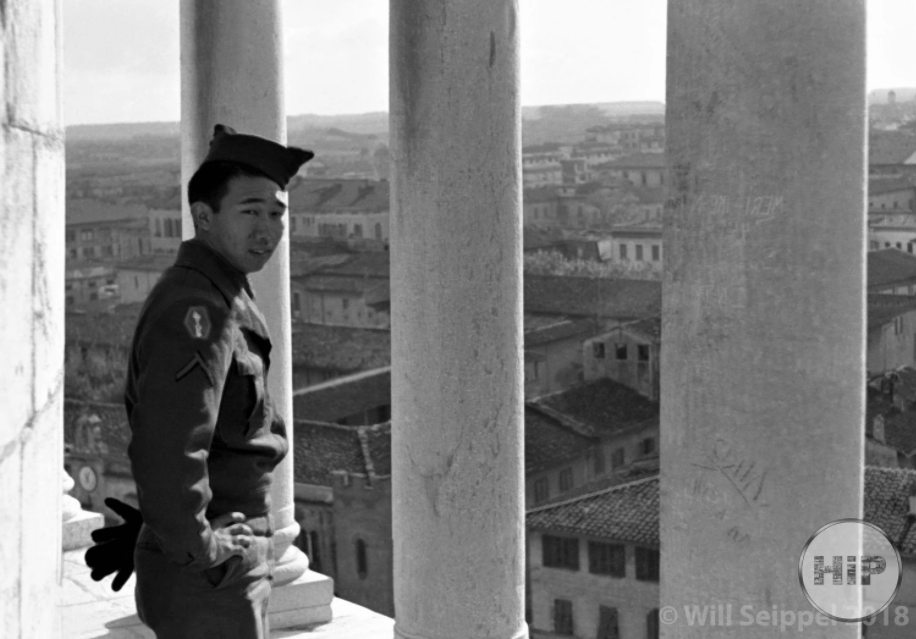

George’s photography is illuminating because it offers a rare window into what it was like to be a Nisei soldier during the war. His photographs contain many scenes that most people would otherwise never get to witness, like a group of soldiers roasting a pig in a deserted house in Italy or the faces of the many Nisei who showed such tremendous bravery.

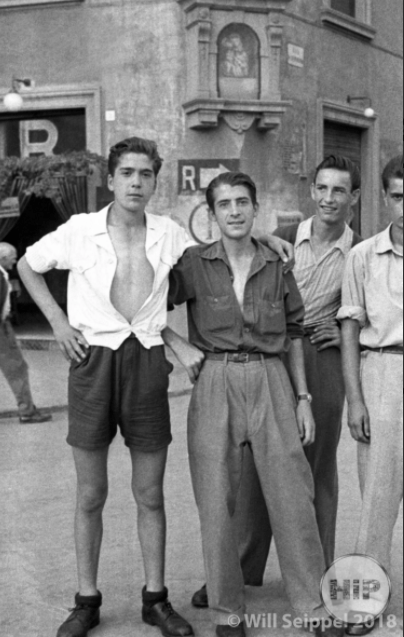

A Street Photographer in War-Torn Italy

In addition to their documentary value, George’s photographs — perhaps because they were snapped quickly while he was on the move — foreshadow the stylistic elements that would come to define the street photography movement. Many of George’s photographs are spontaneous, unposed snapshots from the streets of Italy, and in many respects, they resemble the classic street photography styles that were popularized by photographers like Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander. Street photography, which reached its heyday in New York City in the 1960s, embraces the chaos, conflict, and accidental beauty of bustling urban spaces. Subjects are often unaware of the camera’s presence, and photographers use a fast shutter speed and fast film to capture striking photos of humming public spaces. Street photography’s best practitioners have a way of zeroing in on little details and infusing a sense of strangeness to even the most mundane elements: shadows on a sidewalk, the shape of a woman’s hair, the juxtaposition of street signs and advertisements.

George Sakata’s snapshots of wartime Italy function in much the same way. His photographs have a certain eerie appeal to them. On the one hand, we see many of the same images that any tourist might photograph on a typical vacation: the Colosseum, formidable churches, brilliant sunsets. Some snapshots suggest a sense of normalcy: a man getting a shave at the barbershop, children grinning.

Candid Photos Infused with Emotion

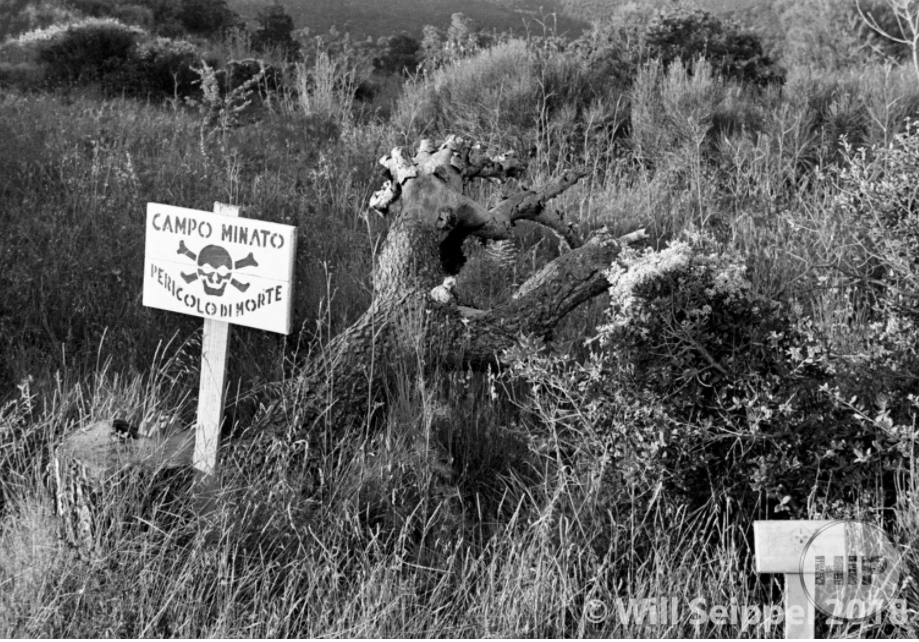

But alongside these light and breezy moments are other images that reveal another dimension of these spaces. In these photos, we see an Italy that is far from ordinary. These include a snapshot of a nearby minefield and photos of rubble and ruins. Some compositions are subtle enough to convey the desperations of war. For instance, we see two children manning a shoeshine box, waiting for customers, perhaps desperate to earn enough to buy food. In another shot, a little boy huddles in a cart of watermelons.

I’m surprised over and over again by the haunting juxtaposition of moods in Sakata’s work. Children smiling, women shopping — all of it mixed in with the obvious trademarks of war. Scrolling through Sakata’s work can be a jarring experience, for his subject matter quickly shifts between the casual and the catastrophic.

Sometimes Sakata’s photographs are full of activity — friends clustered on sidewalks, busy markets. But there are just as many photographs that have a certain emptiness to them. They feature deserted outdoor bars, vacant alleyways, decimated structures. The activity within Sakata’s work is almost perfectly balanced by these moments of eerie stillness. His quieter snapshots remind us of those absent: the missing men replaced by signs for minefields, the destroyed homes, the lost friends. This is Italy at war, somehow familiar and alien at the same time.

Two Worlds Colliding, Captured in One Photo

Perhaps my favorite photograph is the one below, which we’ve christened “Strangers and Soldiers.” In this photo, a man and woman appear to be conversing at the center of the frame. Perhaps they are unaware of the camera’s presence, or perhaps they are ignoring it on purpose. In any case, they turn away from the camera. On the right side of the frame, a soldier passes them, his gaze connecting with the camera, if only for a moment. I love the two worlds that seem to be colliding here: the Italian couple, who appear to carry on with life as usual, and the soldiers, who symbolize the radical upheavals within the country and the world. In a way, this photograph is emblematic of Sakata’s whole body of work, which hearkens back to life as we know it while also highlighting evidence that the world was anything but. This juxtaposition of the strange and the familiar, the sweet and the staggering, the smiles and the emptiness, is why I’m such a big fan of Sakata’s wartime photographs.

Sakata, a Quiet Hero

I wish we knew more about these photographs and more about the man who took them. When I reached out to some of George’s family members in the course of my research, they told me that George hadn’t shared much about this particular part of his life. He did not discuss the heroism, the devastation, or the discrimination that he experienced. Perhaps he didn’t think anyone would want to hear about these hard times, or perhaps such stories were too painful to retell.

That’s what I like most about these photographs: their power to shed light on a story that George did not tell. Although he was hesitant to speak about these experiences, we hope his photos can offer a glimpse into his life and into the lives of the many Nisei who fought so valiantly. We do not know how George would have chosen to tell his story, but at least we can get a sense of the world as George saw it, and to us, that experience is priceless.

Read more

American Hero, American Artist: The Legacy of George Sakata

Posted by Allison Radomski on

This Memorial Day, as our nation honors those who have served in our military, the team at HistoryInPhotographs.com (HIP) would like to use this occasion to share a bit more about one such hero: George Sakata, an American soldier and photographer whose work is featured on our HIP site.

From the Sugarcane Fields of Hawaii to California

George was born in Pocatello, Idaho, in 1922. However, the story of his life and his photographs begins long before his birth. It started in the 1860s when Japanese immigrants began arriving in Hawaii to work on its burgeoning sugar cane plantations. During this chapter, exploitation and hardship were typical for this community. Large commercial interests held serious sway in Hawaii, and the sugar cane industry demanded grueling physical labor from the Japanese workers that it depended upon. Immigrant workers could even be fined or whipped for simply talking or taking a break to stretch during their long, arduous workdays.

It wasn’t until the turn of the century that Japanese immigrant families like George’s began to create homes in the Mainland U.S., mainly along the West coast. Once again, Japanese workers had no choice but to take undesirable jobs in mines and in railroad construction. On top of this physical exploitation, Japanese immigrants experienced broad discrimination. They were barred from citizenship, which meant that they were unable to own any land. They were also barred from participating in the American labor movement, which made it difficult, if not impossible, for them to demand better working conditions and fair wages. Japanese immigrants were also victims of riots and violence, and many communities made it painfully clear that Japanese families were not welcome in their neighborhoods. This is the world that George was born into in 1922.

From Hardworking Immigrant to a U.S. Internment Camp

Although this type of discrimination was the unfortunate norm throughout George’s childhood, the Japanese immigrant community faced even greater struggles in 1942. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the incarceration of Japanese families. As a result of this order, about 120,000 Japanese Americans were forced to leave their homes and relocate to squalid internment camps scattered across the western United States. Relocation also required the forced liquidation of assets, so evacuees had no choice but to sell whatever possessions they couldn’t carry. In exchange, they were placed indefinitely in prison compounds surrounded by snipers and barbed wire.

At that time, George, his parents, and his younger brother lived in Glendale, California. Around his 20th birthday, George and his family arrived at the Manzanar War Relocation Center, an internment camp located just north of Death Valley. Manzanar was an especially difficult camp because of its punishing desert climate. In addition to the camp’s communal latrines and cramped barracks, Manzanar’s prisoners had to deal with scorching temperatures that could reach over 110 degrees Fahrenheit. Relentless desert winds filled the camp with sand and dust, and the winter months were no better. Below-freezing temperatures were common, making the winters just as miserable. By September 1942, around 10,000 Japanese Americans were living at Manzanar.

Internment Camp Prisoner to War Hero

In the early years of World War II, Japanese Americans were prohibited from military service, but by 1943, this policy had changed. More than 30,000 second-generation Americans of Japanese descent — also known as Nisei — served in the United States military during World War II. George Sakata was one of them.

George filled out his draft card in 1942, shortly after his arrival at Manzanar, and within the next year or so, he became a member of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The 442nd RCT was a segregated unit that consisted entirely of Nisei soldiers. Because of their Japanese heritage, these particular soldiers were treated as expendables, and they received especially risky assignments. Even so, the 442nd accepted these challenges, matching the adversities of war with their tenacity. Their motto became “Go for Broke.”

Defying dangerous odds, the Nisei soldiers secured significant victories for the Allied forces. In 1944, the 442nd worked its way across Southern France, liberating various towns from Nazi occupation. They were also active throughout Italy, partnering with the 92nd Infantry Division (a segregated African American soldier unit) to push Nazi forces back across the border.

Perhaps their most famous victory was the successful rescue of the Lost Battalion. In October 1944, the 1st Battalion of the 141st Infantry, also known as the Texas Battalion, became surrounded by German forces in the Vosges Mountains. Although other battalions made multiple rescue attempts, none succeeded. About 275 soldiers were trapped, and their chances of survival became increasingly grim.

The 442nd RCT was sent in as a last-ditch effort to save the doomed battalion. After several days of harrowing combat, the 442nd broke through the German forces and rescued the 211 surviving members of the Lost Battalion. During their entire Vosges campaign, which also included the liberation of Bruyeres and Biffontaine,160 members of the 442nd RCT were killed, and 1,200 were wounded.

It would not be the first or the last time that these Nisei soldiers would take great risks and suffer severe casualties on behalf of their country. In recognition of their bravery, the unit was awarded more than 4,000 Purple Hearts, 560 Silver Star Medals, and 21 Medals of Honor. To this day, the 442nd remains the most decorated unit for its size and length of service in all of U.S. military history.

George Sakata was one of these men. Like so many Nisei soldiers, he served his country courageously and made incredible sacrifices for the United States. After World War II, George returned home to the U.S. He married, had children, and built a career as a mechanical engineer.

A Fresh Perspective on the War

Here at HIP, we don’t know as much about George’s story as we might like, primarily because he, like so many Nisei veterans, didn’t talk to his family and friends about his accomplishments or the dangers of his deployment. While we were able to find some of his family online and also discover more information via Ancestry, George passed away in 2009, so there is much that we can never know about him—which is one reason why we’re so excited about George’s photographs.

George was an avid photographer throughout his life, and he had his camera with him during his deployment. After George’s death, HIP’s founder and WorthPoint CEO, Will Seippel, purchased the bulk of George’s photographic negatives, and these include the snapshots that he took throughout World War II.

George’s photography is illuminating because it offers a rare window into what it was like to be a Nisei soldier during the war. His photographs contain many scenes that most people would otherwise never get to witness, like a group of soldiers roasting a pig in a deserted house in Italy or the faces of the many Nisei who showed such tremendous bravery.

A Street Photographer in War-Torn Italy

In addition to their documentary value, George’s photographs — perhaps because they were snapped quickly while he was on the move — foreshadow the stylistic elements that would come to define the street photography movement. Many of George’s photographs are spontaneous, unposed snapshots from the streets of Italy, and in many respects, they resemble the classic street photography styles that were popularized by photographers like Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander. Street photography, which reached its heyday in New York City in the 1960s, embraces the chaos, conflict, and accidental beauty of bustling urban spaces. Subjects are often unaware of the camera’s presence, and photographers use a fast shutter speed and fast film to capture striking photos of humming public spaces. Street photography’s best practitioners have a way of zeroing in on little details and infusing a sense of strangeness to even the most mundane elements: shadows on a sidewalk, the shape of a woman’s hair, the juxtaposition of street signs and advertisements.

George Sakata’s snapshots of wartime Italy function in much the same way. His photographs have a certain eerie appeal to them. On the one hand, we see many of the same images that any tourist might photograph on a typical vacation: the Colosseum, formidable churches, brilliant sunsets. Some snapshots suggest a sense of normalcy: a man getting a shave at the barbershop, children grinning.

Candid Photos Infused with Emotion

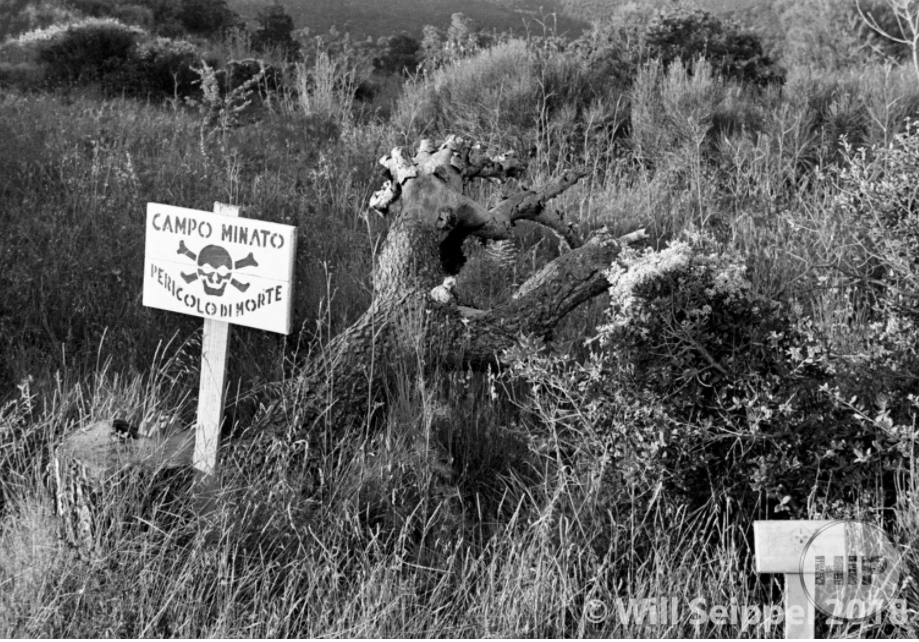

But alongside these light and breezy moments are other images that reveal another dimension of these spaces. In these photos, we see an Italy that is far from ordinary. These include a snapshot of a nearby minefield and photos of rubble and ruins. Some compositions are subtle enough to convey the desperations of war. For instance, we see two children manning a shoeshine box, waiting for customers, perhaps desperate to earn enough to buy food. In another shot, a little boy huddles in a cart of watermelons.

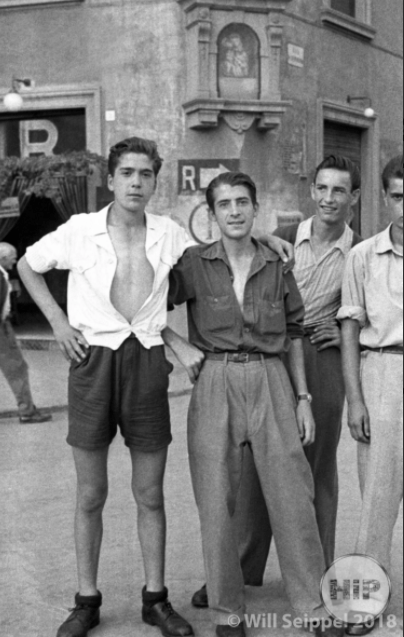

I’m surprised over and over again by the haunting juxtaposition of moods in Sakata’s work. Children smiling, women shopping — all of it mixed in with the obvious trademarks of war. Scrolling through Sakata’s work can be a jarring experience, for his subject matter quickly shifts between the casual and the catastrophic.

Sometimes Sakata’s photographs are full of activity — friends clustered on sidewalks, busy markets. But there are just as many photographs that have a certain emptiness to them. They feature deserted outdoor bars, vacant alleyways, decimated structures. The activity within Sakata’s work is almost perfectly balanced by these moments of eerie stillness. His quieter snapshots remind us of those absent: the missing men replaced by signs for minefields, the destroyed homes, the lost friends. This is Italy at war, somehow familiar and alien at the same time.

Two Worlds Colliding, Captured in One Photo

Perhaps my favorite photograph is the one below, which we’ve christened “Strangers and Soldiers.” In this photo, a man and woman appear to be conversing at the center of the frame. Perhaps they are unaware of the camera’s presence, or perhaps they are ignoring it on purpose. In any case, they turn away from the camera. On the right side of the frame, a soldier passes them, his gaze connecting with the camera, if only for a moment. I love the two worlds that seem to be colliding here: the Italian couple, who appear to carry on with life as usual, and the soldiers, who symbolize the radical upheavals within the country and the world. In a way, this photograph is emblematic of Sakata’s whole body of work, which hearkens back to life as we know it while also highlighting evidence that the world was anything but. This juxtaposition of the strange and the familiar, the sweet and the staggering, the smiles and the emptiness, is why I’m such a big fan of Sakata’s wartime photographs.

Sakata, a Quiet Hero

I wish we knew more about these photographs and more about the man who took them. When I reached out to some of George’s family members in the course of my research, they told me that George hadn’t shared much about this particular part of his life. He did not discuss the heroism, the devastation, or the discrimination that he experienced. Perhaps he didn’t think anyone would want to hear about these hard times, or perhaps such stories were too painful to retell.

That’s what I like most about these photographs: their power to shed light on a story that George did not tell. Although he was hesitant to speak about these experiences, we hope his photos can offer a glimpse into his life and into the lives of the many Nisei who fought so valiantly. We do not know how George would have chosen to tell his story, but at least we can get a sense of the world as George saw it, and to us, that experience is priceless.