My parents recently moved out of my childhood home. I traveled back to Texas to help with the endeavor, sifting through drawers and boxes, trying to help them pack up their lives as best I could. Admittedly, I was a slow assistant—too often spending time carefully rummaging through paperwork and files, savoring the opportunity to get a glimpse of what my parents’ lives were like before I was born. I couldn’t help myself. In packing their oversized house, I found enough photographs to fill over a dozen boxes. Old snapshots of my dad playing rugby in the 70s, images from their fishing trips to the Florida Keys, photos of family gatherings from before I existed. While the mysterious histories behind these images were certainly intriguing to me, I found myself equally engrossed in the photos themselves, which were often arresting.

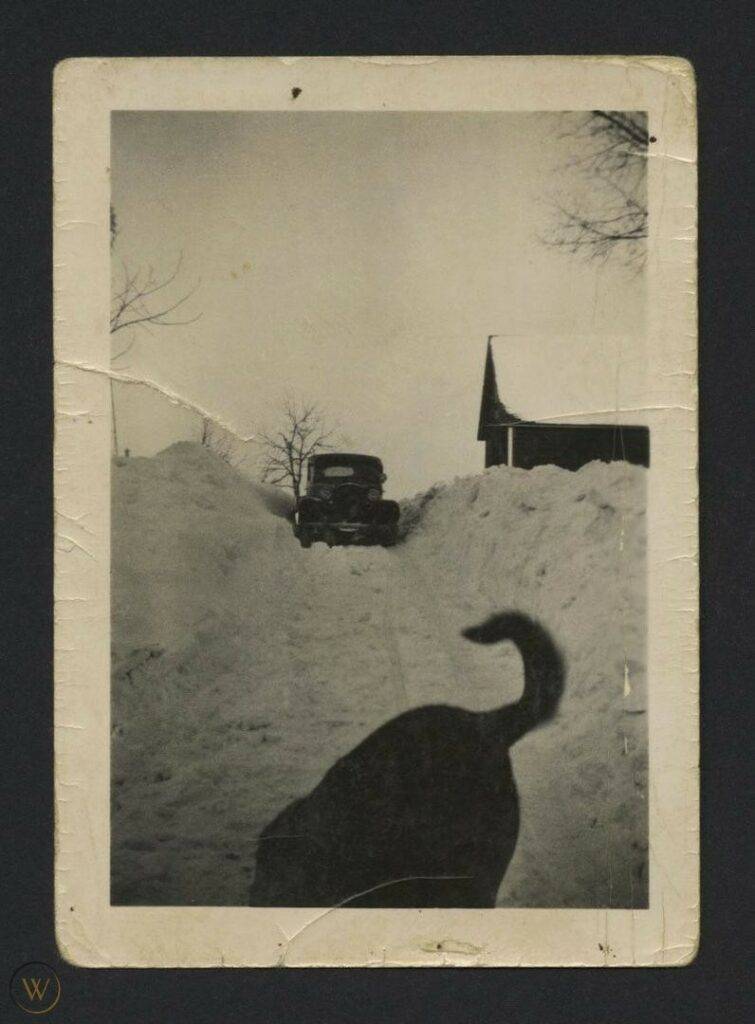

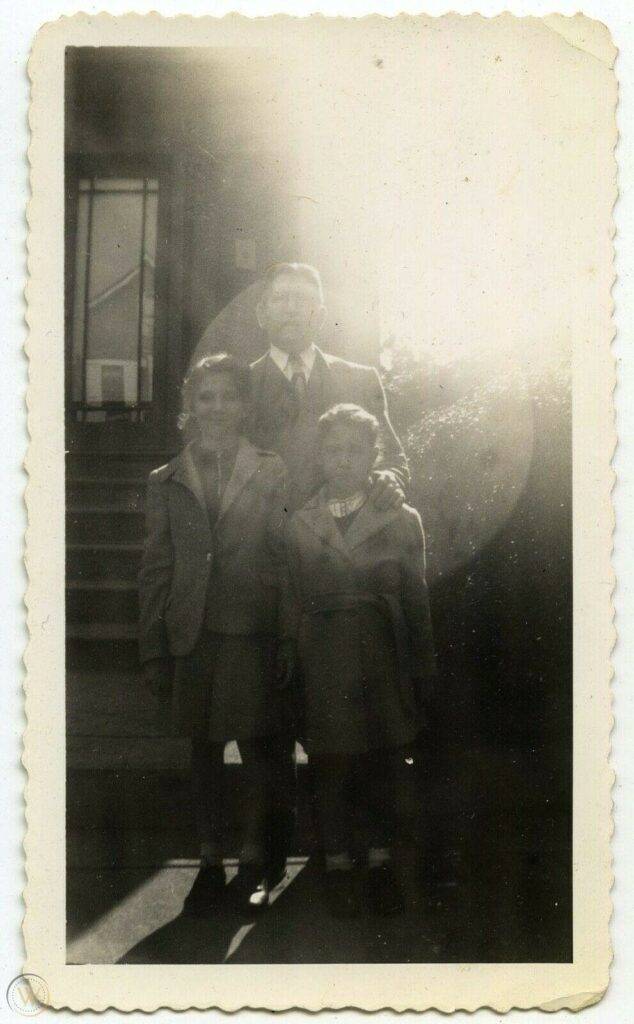

I say arresting because I found myself drawn to their flaws. Clearly, my family is not filled with skilled photographers, as there were hundreds of imperfect photos. A thumb in the way, an overexposure, an image out of focus. Although these were mundane images, they felt so completely outside of the modern experience. Looking at these photos, I realized how much I missed imperfect images and how I rarely see photos like these anymore. Now the ugly bits have been Photoshopped out and filtered into oblivion. The fingers have been deleted, and these days, most people seek permission before posting an image someone could find even remotely unflattering.

Recognizing Imperfections

There are many common “imperfections” in photography, all small accidents leading to unexpected results. While most people I know quickly delete an ugly image or toss a bad print, I think there is a great beauty in these unanticipated occurrences that deserves recognition.

Misfires. Misfires still happen today, but the name harkens back to the days of film: A misfire is an accidental image created by a slip of the trigger finger, which activates the shutter. Misfires capture the unexpected. These visuals are special precisely because they are not meant for posterity. They are liminal moments—discarded images sandwiched between the “real” photos—not meant to be remembered. These imperfections speak to an authenticity and sincerity that can sometimes feel lacking in the digital age. They also speak to life—to the imperfections and disappointments, unexpected moments, and happy accidents that make up our lived experience.

Out of focus. Sometimes you focus on the wrong object, or your focal length is incorrect, or the depth of field is all off. Maybe the image is low resolution in today’s terms, or the file deteriorated, compressed, remixed, snapshot-ed, and shared. The pixels are more visible, with lots of noise and grain. These photographs beautifully undermine the indexicality of the medium. They are no longer a mimetic depiction, as the indexicality has been shifted from capturing a visual experience of the subject to a physical experience of the medium. Now the focus has moved onto the act of photographing, not the documentation of the moment. No longer is the work a conversation about the depiction, but about the photographer’s choices, process, and “failures.” A shifting of focus literally shifts attention, drawing our eyes to the unexpected, highlighting things we may not have otherwise seen.

Under and Overexposure. Perhaps one of the issues we most commonly fight in the digital age, exposure problems persist even with the help of technology. Overexposure leaves us with blown-out images, where details are lost in bright whites. Its cousin, underexposure, leaves us with inky, blocky blacks, which obscure the details of the image. While these problems all speak to mechanical issues, phones without the needed sensitivity for the lighting (or photographers sampling light in the wrong areas) can also produce this ephemeral quality. Difficult to replicate, exposure issues change how we relate to an image by evoking moods and readings that otherwise may not have been present.

Odd Compositions. Even if we can’t readily identify different composition rules, like the rule of thirds, we naturally can sense when a composition is “off.” Maybe the action is too close to the edge of the image, or a person’s head is cropped off. In the era of image saturation, we can all immediately recognize when an image is “wrong,” and thus, we have come to expect and value certain visual compositions over others. But there is a case to be made for the unusual composition —the one that leaves out details and raises questions. These compositions ask to be seen, not merely looked at, and they demand a more active engagement from the viewer.

Embracing Imperfections Across the World of Collecting

Numismatists, or coin collectors, have come to highly value errors in coins. Mint-made errors, or mistakes made in the minting process, are some of the most highly sought-after characteristics in coins. If the imprinting process produces unexpected results, like an offset design, these unintended mistakes become more valuable as their unique, rare quality is seen as a marker of beauty. The “error” here is a desirable trait because it stands in stark contrast to the uniformity of the other coins. As the images we consume become more tightly controlled, more carefully manipulated to produce slick, professional results, an argument must be made to embrace the imperfect image.

All of the aforementioned imperfections, and others like light leaks and multiple exposures, remind us of the photographic process. They remind us that ultimately photography presents us with mediated, authored images. Imperfect images break the camera’s illusion of objectivity by showing the flaws in the system.

So, go ahead and frame the “bad” family portrait. Post an unfiltered image taken from the hip. Use a crappy camera with two settings, where the flip of a coin determines depth of field. Use expired film, and don’t toss your parent’s ugly photographs. It is time for our perfectly Photoshopped world to be reminded of the value of imperfection.

Megan Shepherd is a curator, freelance writer, and artist. She has worked in fine art museums for a decade and holds two master’s degrees in the field. When she takes a break from art, she enjoys science-fiction books, antiquing, backpacking, and eating her weight in Dim Sum.

This article was originally published by WorthPoint on WorthPoint.com