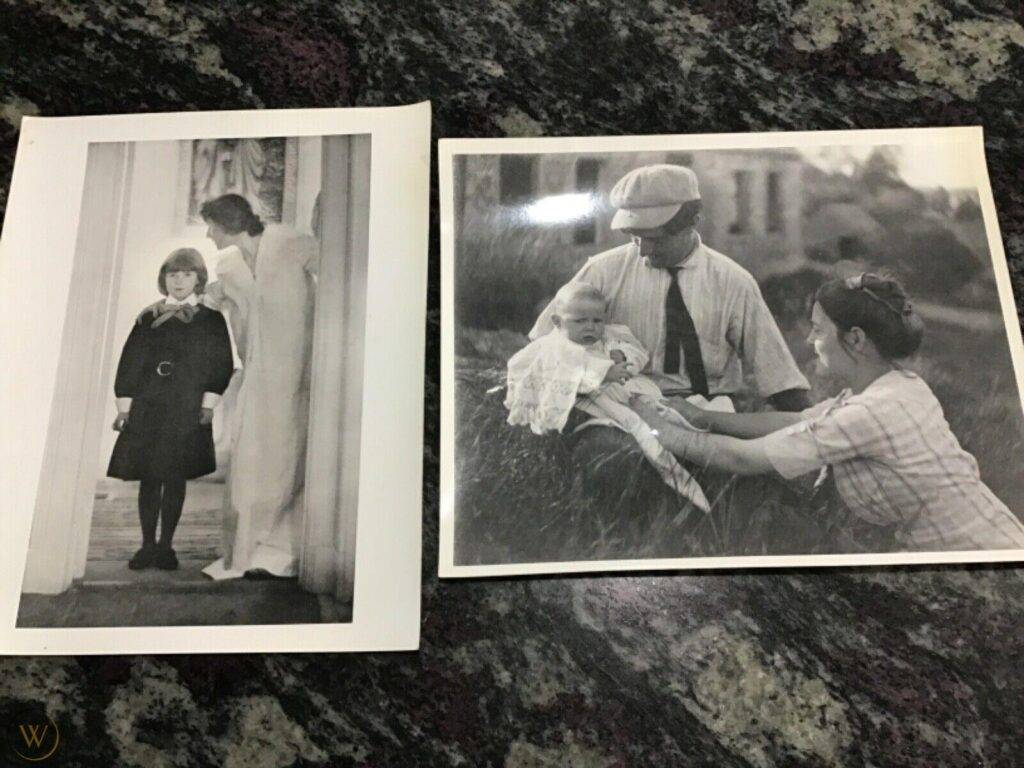

With Women’s History Month already at its close, we at History in Photographs have been thinking about the role of women in early photography, and in particular, two women who are represented within our collection of negatives: Alice Curtis and Martha Hale Harvey. But before we dig into the stories of these two photographers, both of whom were active in the New England area between 1880 and 1920, we’d like to offer you a bit of background on the history of women in photography. Throughout the evolution of the medium, women have received far less attention and analysis than their male peers, which means that there’s often a lot less information available on their lives and work. However, even in photography’s earliest years, women immediately embraced this new technology, pushing the boundaries of the medium right alongside their male counterparts.

Pictorialism & Photo-Secession

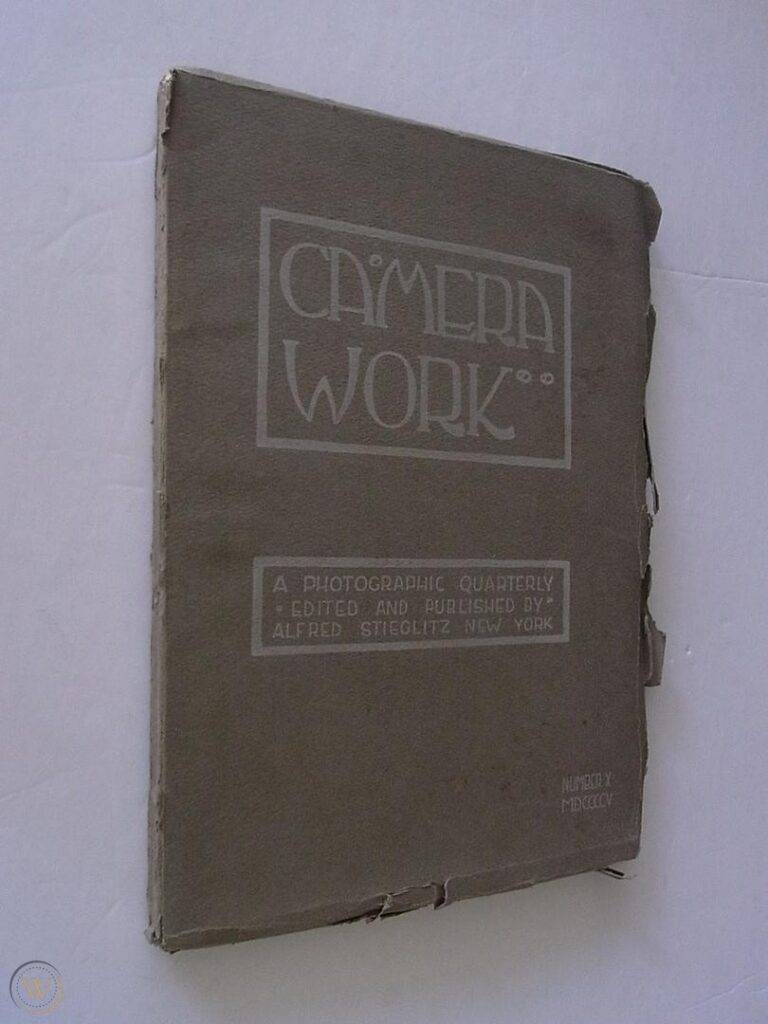

As photography gained popularity at the end of the 19th century, a growing number of photographers wanted their medium to be taken more seriously as a fine art. This desire fomented the rise of Pictorialism, a movement within turn-of-the-century photography that embraced the manipulation of photographic materials as a means of greater personal expression.

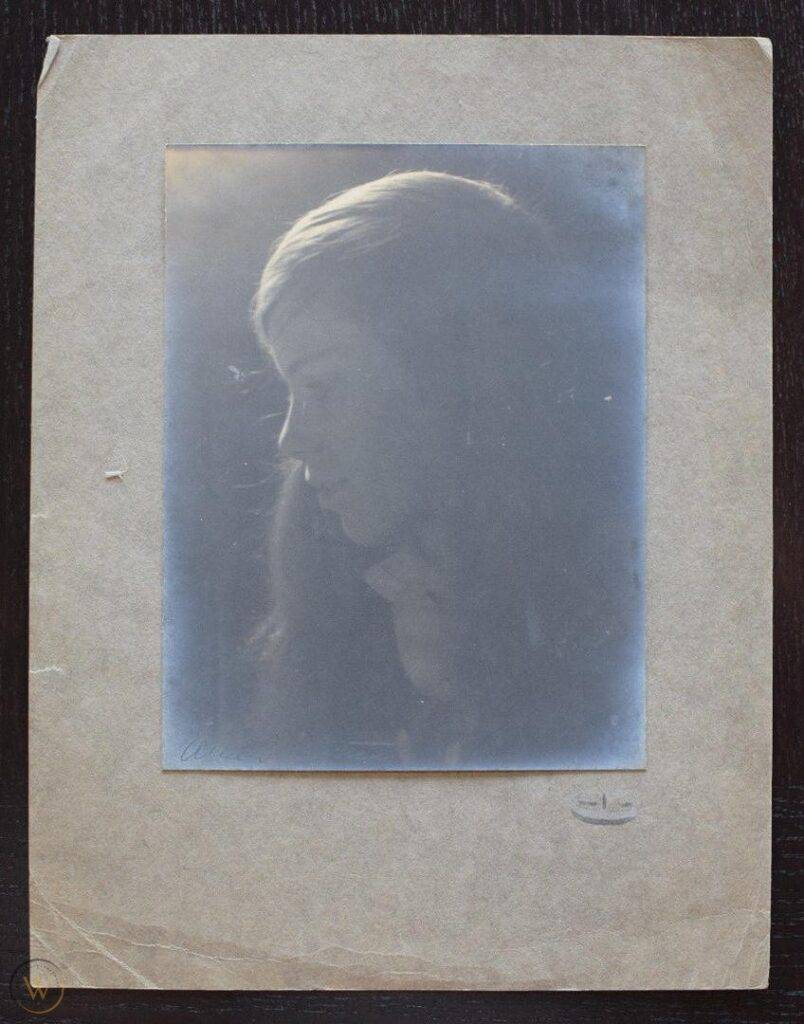

What set the Pictorialists apart from other photographers was their emphasis on aesthetic intervention. In other words, Pictorialists didn’t want to simply document the world through mechanical means. They wanted to create their own unique vision of it by manipulating their medium in new and distinctive ways. Pictorialist photographers believed these interventions, often done within the darkroom, proved that photography was about more than just replicating a subject’s likeness. By demonstrating the medium’s artistic flexibility, Pictorialists sought to prove that photography should be on the same playing field as painting and sculpture. Pictorialists also attempted to achieve this aim by creating photographs that, in their opinion, bore a greater resemblance to paintings. For this reason, many Pictorialist photographers embraced romantic imagery and the use of soft focus in order to recreate a fine-art aesthetic.

A prominent group of pictorialists, dubbed the Photo-Secession led by Alfred Stieglitz, included many women prominently within the organization. Stieglitz, the husband of Georgia O’Keeffe, was a very famous photographer within the early 20th century and was instrumental in photography’s early decades as a fine art medium. A small group of New York-based photographers founded the Photo-Secession in 1902, which included two women, Gertrude Käsebier and Eva Watson-Schütze.

Gertrude Käsebier came to photography after raising three children, with motherhood and marriage often figuring within her visual narratives (in fact, she hilariously entitled an image of two bound oxen “Yoked and Muzzled – Marriage”). Perhaps her most famous series of images are her portraits of Native Americans, including many Sioux photographed while they were traveling with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. These images show a respect and sensitivity that was, unfortunately, uncommon towards Native Americans at the time.

The other female co-founder of the Photo-Secession was Eva Watson-Schütze, who was known for her striking, soft-focus portraits of female subjects. Based in Chicago, she was one of the few founding members not based in New York, and her career-focused nature was bound closely with feminist ideas of the time. She believed that an artistic reckoning was imminent and that it would have women and photography at its center: “There will be a new era, and women will fly into photography.” While not founders of the movement, many other female photographers of this era were also involved with the Photo-Secession to varying degrees, like Mary Devens, Sarah Ladd, Ann Brigman, and Alice Boughton.

Feminism and feminist beliefs were popular with many of these early female photographers. Alice Boughton was a member of the Photo-Secession and also the New Woman movement, which emphasized a woman’s independence in mind, body, and spirit. New Woman members sought to challenge male-dominated society, asserting that women deserved to be treated as equals and to be seen as artistic peers. In fact, many women in this time period used photography as a means of expressing this independence.

While not directly involved with the Photo-Secession, Zaida Ben-Yusuf was an English-born New Yorker who rose to prominence in the first few decades of the 20th century. She was a highly sought-after portraitist, known for photographing the most famous (and the wealthiest) in America, including future Presidents like Grover Cleveland and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Her work was included in just about every major American publication of the era, including The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies Home Journal, and The Cosmopolitan Magazine. She was even a spokeswoman for the Eastman Kodak Company.

Focusing on the Future

While it is easy to see the role women played in the early decades of photography, their contributions are still overlooked, willfully ignored, or simply forgotten even today. At the time, it was often unseemly for women to pursue such a profession, and even once it was no longer taboo, women faced many barriers within the field. Women’s work was regularly referred to as “inferior” and early art historical narratives place much greater emphasis on men. Women’s careers were also subject to the demands of family and relationships, with marriage typically dictating the end of a woman’s professional photography career. Luckily, not all information was lost and many of the wonderful images shot by these photographers still exist. In the 21st century, we have seen a movement towards repairing the damage caused by the art historical canon’s almost exclusively male emphasis.

Here at HIP, we’re excited to continue the conversation about women in photography and to help elevate their role within the public consciousness. Keep your eyes peeled—we’ll have more images and more stories of women photographers coming soon.

Megan Shepherd is a curator, fine art appraiser, freelance writer, and artist. She has worked in fine art museums for a decade and holds two master’s degrees in the field. When taking a break from art she enjoys science-fiction novels, trail running, and quilting.

This article was originally published by WorthPoint on WorthPoint.com