“See those kids right there? That’s what I used to do.” Larry Kellogg is referring to a photograph of a dozen or so children unloading a massive container full of circus gear.

“I was one of those kids who never cared about sports or anything. As early as I can remember, I just loved the circus. And when the circus would come to town, I’d be there. I’d help put up the tent to earn a free ticket. Then, after the circus left town, I’d go around to all the stores and ask if I could have their circus posters. Back then, my bedroom walls were covered with circus posters.”

You can still hear the youthful zeal in Larry Kellogg’s voice. He’s an expert on circus memorabilia thanks to his long career in the circus industry. For more than three decades, Larry worked as a publicist for Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey, and he also worked as Communications Manager for the show’s theme park in Florida. For the last 50 years, Larry has done research and consulting for the Ringling Circus Museum in Sarasota. As I began trying to figure out the stories behind the various circus negatives we have at History in Photographs, I knew that Larry was the expert to ask.

Then again, it’s not Larry’s trove of knowledge that I most enjoy. It’s his palpable circus love that really conveys the story of these images.

“Lots of kids would show up and work for a free ticket, and we did all kinds of things,” Larry explains. “One year, I helped lace up the tent. I had to stitch together two big sections of fabric.”

Something about this statement seems incredulous to me: a child stitching together a colossal tent? I ask Larry how old he would have been when he performed such a crucial job.

“Oh, I don’t know,” he says. “Maybe 11, 12, 13?”

Cleary the circus heyday was a different era and in more ways than one. The Ringling Brothers and P.T. Barnum began their respective traveling shows in the late 19th century, well before the advent of all the things we associate with entertainment today.

“The circus was the number one pop culture event of the time,” Larry explains. “That was it. It was popular music. It was the precursor to the movies. It was everything.”

“That’s why you see so many circus photos,” Larry adds. “There were professional photographers in different towns and of course they’re always looking for new things to photograph. When the circus comes, you have to shoot that.”

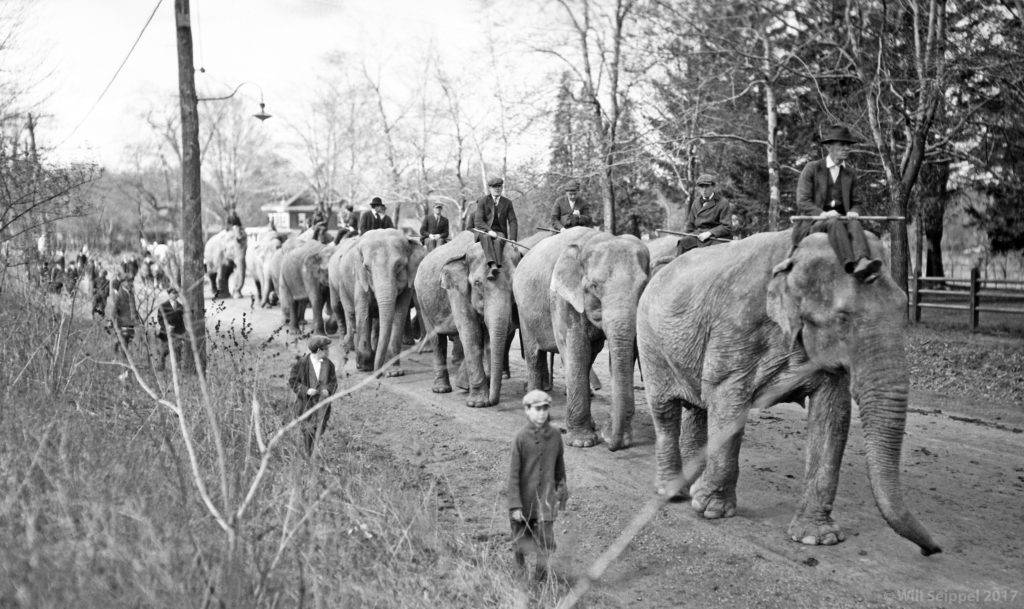

And it wasn’t just the show itself that drew spectators. “Back in the 1930s and 40s, simply watching the circus arrive was a big deal. Thousands of people would show up to watch them unload off the trains.”

The arrival still managed to draw crowds even in the show’s twilight years. “Back in the 1990s, I flew up to New York City because people kept telling me that I just had to see the circus unload there. It’s special because when they unload, the animals walk under the tunnel and come out in Manhattan. I mean, it’s midnight and you have all these camels and elephants walking through the tunnel and into the city. There are thousands of people out in the middle of the night just watching as the animals make their way to Madison Square Garden.”

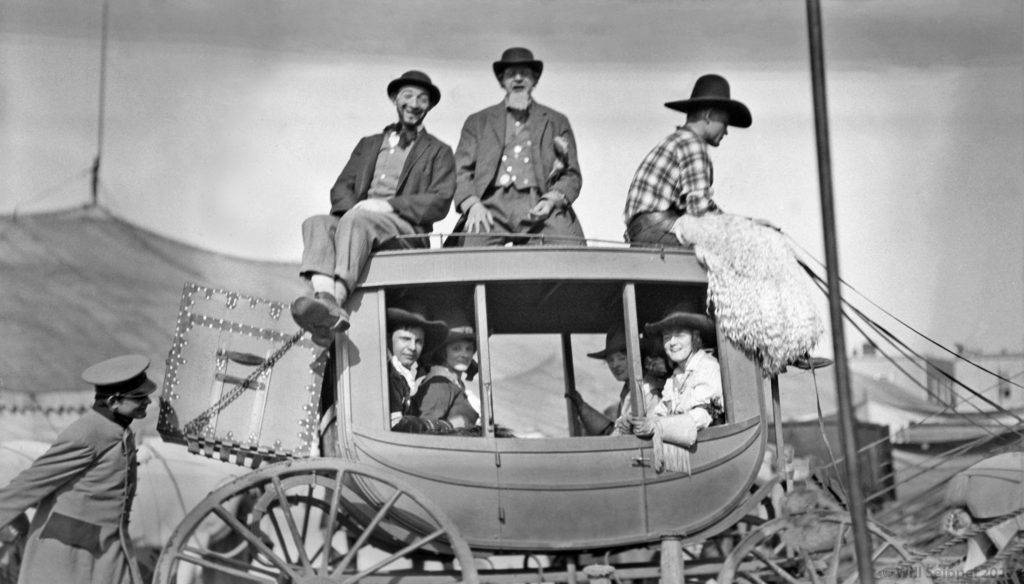

Watching the arrival was just the beginning. “There was also a daily street parade. It was like an advertisement. That’s what we’re seeing here,” Larry says, referring to a series of photographs that feature elaborate floats with scenes of Ancient Egypt and China.

“They stopped doing the daily street parade in the 1920s because that was when towns started paving their streets,” Larry adds, referring to the dirt roads in various parade photos. “There were wagons that weighed tons and had steel wheels, so sometimes the floats would actually break the pavement.” (Click here to read more about the largest wagon in the world, which required 40 horses to move.)

“These wagons were introduced for the first time in 1903,” Larry explains. “They were beautiful, made of hand-carved wood. You can still see some of the original wagons at the Ringling Circus Museum in Sarasota and at the World Circus Museum in Baraboo, Wisconsin.”

Awe for the circus animals was another motivator for circus photographers. “People in small towns hadn’t seen an elephant before,” Larry explains. “They hadn’t seen any of these animals because they didn’t have zoos. It was all new to them.”

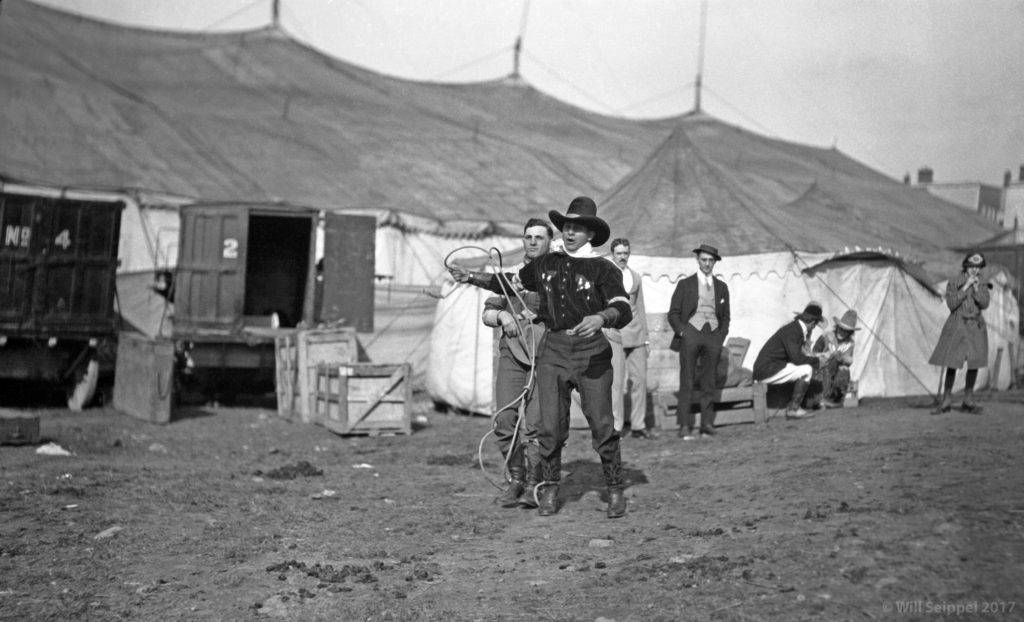

“There was an aftershow too,” Larry adds. “People could pay extra to remain in their seats and see an additional act, usually some kind of western. The aftershow often had big names attached so people would want to stay.”

Oddly enough, the circus and the photographic medium seemed to tread parallel paths, growing together and influencing each other. Photography was becoming widespread around the time the circus was born, and the medium enhanced the spectacle experience. Some of the most common forms of circus photography were the cabinet card and the carte de visite, which were small photographs of individual performers that were sold as souvenirs. (Click here for Larry’s discussion of these two formats.)

Photographs were especially lucrative for the circus sideshow. “You’d pay twenty-five cents to get into the sideshow and that’s where you’d see certain acts like the Giant and the Sword-Swallower. Each of them would have a platform and they’d sell postcards of themselves. You could buy a postcard of the Siamese Twins. You could buy a postcard of the Fire-Eater. Each person sold things for extra money.”

P.T. Barnum even had a permanent museum in New York City, which just happened to be right across the street from Mathew Brady’s famed portrait studio. When Barnum’s performers needed their picture taken, all they had to do was cross the street. Today, those types of postcards typically sell for around $100.

Other circus photos include large glossy images used for publicity. “Those only sell for around $5 each,” Larry adds. “They’re not worth as much.”

The most valuable circus photos were taken behind the scenes. “All the performers had cameras and those photos are one of a kind,” Larry explains, “Say I’m a performer taking snapshots in the backyard. I go to a local studio, get my set of prints, and that’s it. There aren’t anymore. It’s just that set.”

Behind-the-scenes snapshots are valuable because they offer a unique window into the unseen dimensions of circus culture. “Those types of shots weren’t of the performance, but of the backyard where people were doing laundry or washing their hair or playing checkers,” Larry explains. “Those are the ones that collectors seem to be really interested in.”

All in all, circus photos can range in value from a few dollars to a few thousand. Like most photographs, a circus photograph is more valuable if it was printed around the time it was taken. “For instance, Edward J. Kelty would take pictures of the performers and make the prints in time to sell them back to the performers before they left town,” Larry explains. Those vintage Kelty prints have sold for thousands of dollars. (Read more about Kelty and other famous circus photographers here.)

That example sums up the most important elements to look for when you’re on the market for circus photographs. When it comes to figuring out the value of circus photographs, there are three big variables to keep in mind: the age of a photograph, behind-the-scenes subject matter, and rarity. The most valuable photographs are vintage prints that offer a one-of-a-kind view into the hidden lives of circus performers.

“This is a typical backyard. You see that tent in the background? The one marked band?” Larry says, referring to an image of zebras and tents. “That’s where the band would hang out and play cards when they weren’t performing. And that woman sitting in the foreground with her back turned? She was probably just a towner.” The term refers to people who lived in town and were paid to help out. Although the circus had roughly 1,000 crew employees who traveled with the performers, they still took on extra workers from town to town.

Although Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey had its last performance in 2017, the buzz for circus memorabilia is still strong. Back in January, the Freedom Auction Company sold over $200,000 in circus collectibles. It’s a sign that circus zeal is still alive and well. Then again, you can tell that much just by talking to Larry and hearing the sound of his voice as he describes how he felt about the circus as a kid. His career and expertise are signs of the joy he takes in collecting.

“See that kid?” Larry says, referring to a photograph of a little boy walking alongside a procession of elephants and circus employees. “That’s me too.”

Larry Kellogg is WorthPoint’s Circus Memorabilia Worthologist. If you’re interested in plumbing the depths of his expertise, you can find his many WorthPoint articles here.

This article was originally published by WorthPoint on WorthPoint.com